Name it the Smoky Metropolis or the Metal Metropolis. You possibly can even name it, as The Atlantic Month-to-month famously did in 1868, “Hell with the lid taken off.” Pittsburgh was all these issues again within the first a part of the 20th century. A labyrinth of molten metal, smoke-belching furnaces and mountains of black coal, the town was populated by grim-faced, multi-cultural laborers pleased with the stone and steel metropolis they’d constructed. When it got here to boxing, it was already a Metropolis of Champions, producing generations of iron-willed, hard-working expertise whose fistic exploits crammed newspaper columns, document books, and, later, plaques on the Corridor of Fame.

Named for the quiet stream that runs by way of it, the borough of Turtle Creek is a nondescript village wedged between the suburbs of Wilkins Township and Monroeville and blocked off from the Monongahela River by Braddock. If you weren’t conversant in the realm, you may stroll by way of it with out understanding, until you caught sight of the 1600-foot-long George Westinghouse Bridge, named for the engineer and businessman who erected factories close by. It’s Turtle Creek’s solely instantly recognizable landmark. In Westinghouse’s heyday, the realm’s panorama was composed of 1 sprawling manufacturing facility beside one other, all since repurposed or demolished.

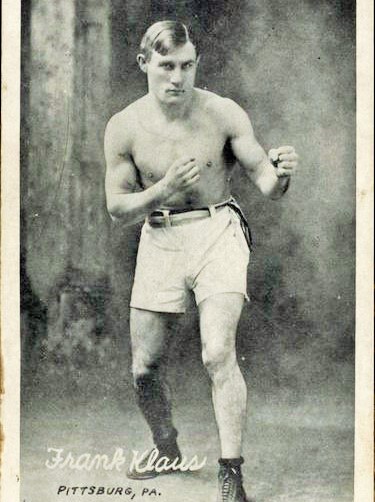

Across the time Westinghouse arrange store there, Frank Klaus, Pittsburgh’s first world boxing champion and born in 1887, would have been studying to stroll in his Turtle Creek dwelling. “Business marks each transfer of the Klaus household,” reported The Pittsburgh Press in 1911, recounting that, as a younger man, Frank would depart his job on the Westinghouse factories and “hurry to the coal pit and swing the sharp choose for a number of hours to assist his Pop,” a German immigrant who operated a coal mine on Oak Hill in close by East Pittsburgh. Profitable road scraps as a teen piqued Klaus’s curiosity in boxing and led him to the Wilmerding Athletic Membership, the place he received two newbie tournaments in two weight lessons, featherweight and light-weight, on the identical night time. This caught the attention of native impresario George Engel, who turned Frank’s supervisor.

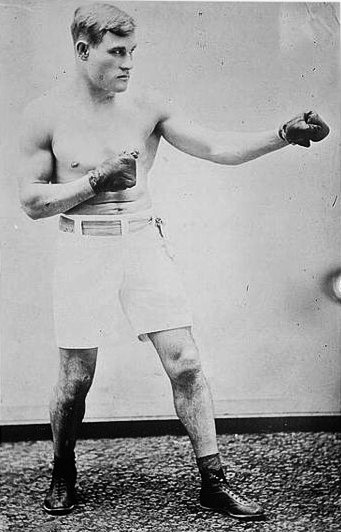

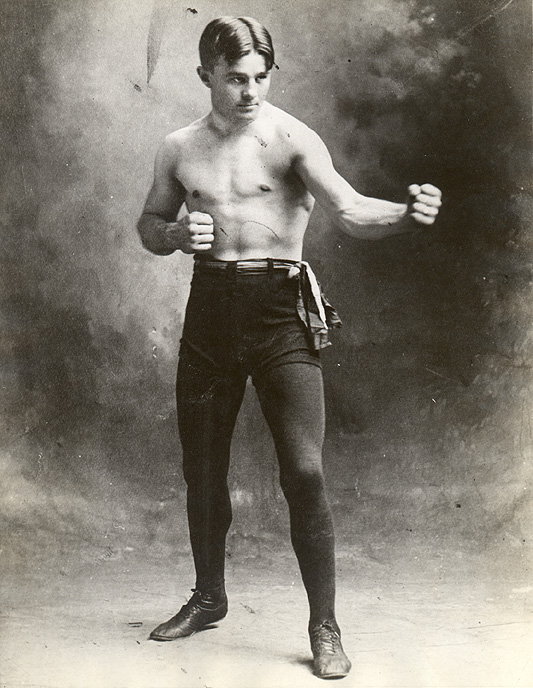

Frank Klaus actually wrote the e-book on infighting, and befitting his simple persona, he titled it merely, The Artwork of In-fighting. “In-fighting is the artillery of pugilism,” he wrote, “as continuous pounding on the partitions of the enemy’s protection steadily reduces him to capitulation.” In different phrases, arduous work and persistence. Retaining with the household custom, trade outlined Klaus’s philosophy for motion within the ring. Constructed of stable muscle, and with a sq. jaw as arduous as something his father may presumably dig out of the earth, Klaus bore into opponents in a methodical however relentless method, a punching machine. He dug his gloves deep into livers and kidneys with a movement and stamina derived from digging his ax into mine partitions for hours on finish as a boy. Regardless of his industrial method, promoters within the cities he visited noticed a extra animalistic high quality in his assault and dubbed him “The Pittsburgh Bearcat.” His fellow Pittsburghers had been extra particular; they referred to as him “The Braddock Bearcat.”

Turning professional in 1904, Klaus turned a neighborhood sensation nearly in a single day, and although he misplaced his sixth professional bout, he then received forty-three straight. Many of those had been no-decision bouts, matches that ended after six rounds with out an official verdict or winner, in accordance with Pennsylvania legislation on the time. A fighter may solely win or lose by knockout or disqualification inside that six-round restrict, and followers relied on their favourite native sportswriter to inform them who received. In Pittsburgh, most favored the loquacious Jim Jab of The Pittsburgh Press. Jab and his fellow columnists noticed just a few losses and attracts for Frank, however dozens of wins.

No-decision fights with former middleweight champions Hugo Kelly and Billy Papke, together with a victory over perennial contender Jack Sullivan in Boston, led to a no-decision, non-title battle with reigning middleweight champ Stanley Ketchel, already a residing legend, his scary energy having put heavyweight champion Jack Johnson on the ground solely months earlier. Earlier than some six thousand spectators at Pittsburgh’s Duquesne Gardens on March 23, 1910, “The Pittsburgh Bearcat” tore into the champion.

Surprisingly, Ketchel, referred to as some of the prepared and thrilling scrappers of the day, supplied little resistance and appeared solely involved with hugging. When he did throw, they had been tender and clumsy punches. Regardless of his personal sincere effort, Klaus was incapable of wounding the clinch-minded Ketchel, and Ketchel made few makes an attempt to harm Klaus. The gang was quickly divided between these jeering the battle as a repair and people headed for the door. As if executing some technique of shock, Ketchel instantly got here alive at the beginning of the sixth and remaining spherical and gunning for a knockout. He discovered Klaus greater than able to commerce, and shortly sufficient Ketchel was again to holding till the ultimate bell.

“Whereas Ketchel was a disappointment Klaus however was entitled to the choice” decided the native Publish-Gazette. Jim Jab of the Publish didn’t mince phrases. He referred to as it “a aromatic frame-up.” “Pity the Pittsburgh sports activities,” he lamented, earlier than declaring that “honors – if such a factor may exist in an occasion of the type – ought to go to Klaus.”

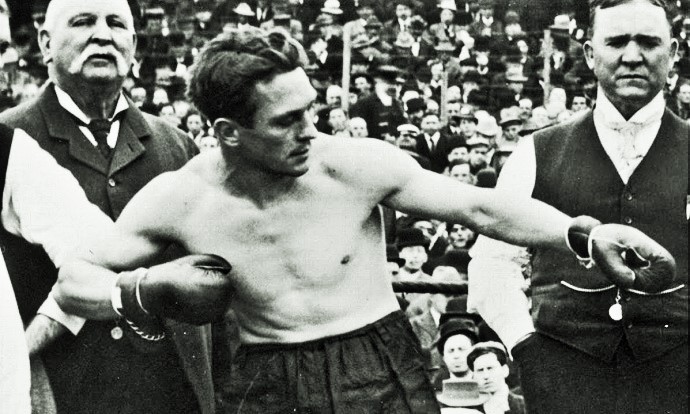

Just a little over six months later, Ketchel was lifeless, murdered by a Missouri ranch hand, and the championship was up for grabs. Klaus was among the many a number of who proclaimed themselves Ketchel’s successor, although common recognition eluded all for a time. In 1912, Klaus and Engel traveled to France, hoping to clear up the confusion by eliminating key middleweights there, not least of which was Papke, the previous champion who had been Ketchel’s chief rival. After wins over future mild heavyweight champ Georges Carpentier and French champion Marcel Moreau, Klaus secured a showdown with Papke for undisputed recognition because the world middleweight king.

On March 5, earlier than the biggest crowd to ever collect on the Cirque du Paris, the ageing Papke boxed cleverly however was rapidly overwhelmed by Klaus’s fixed strain, hitting the canvas twice in spherical seven, and the determined former champ resorted to fixed fouling along with his head and elbows. Routinely shouted at by the group, and warned by the referee, he ignored all of it, and so Klaus started to retaliate along with his personal tough ways. Quickly sufficient, heads had been crashing, eyes had been being thumbed, and groins had been being kneed on either side. One witness referred to as Klaus “a caveman” and Papke “a snarling hooligan.” Finally, the referee disqualified Papke and handed Klaus the choice and the championship, to the nice acclaim of the viewers. After, he was awarded a diamond-encrusted championship belt. Maybe most satisfactorily for Frank, he had doubled his winnings by betting on himself earlier than the battle.

In all, Frank Klaus spent about 9 months in Paris, and he loved each minute of it, possibly somewhat an excessive amount of so. He returned to Pittsburgh and a few six months after successful the championship, he misplaced it to fellow Pittsburgher George Chip in a match on the Previous Metropolis Corridor. When Klaus hit the ground from a wild Chip punch within the sixth spherical, George Engel was so surprised, he collapsed and hit his head on the ground. Each fighter and supervisor had been knocked out. After failing to regain the laurels in a rematch, Klaus retired in 1913 at simply 25 years of age. In 1918 a charity occasion lured him again to the ring for a six-round exhibition with the town’s latest fistic star, Harry Greb, however after that Klaus by no means fought professionally once more.

Years later, when requested why he had light so rapidly, Frank replied, “being the toast of the Paris boulevards didn’t assist.” A hotelier in retirement, Frank Klaus died of a coronary heart assault in his dwelling on February 8, 1940 on the age of sixty and was laid to relaxation at All Saints Braddock Catholic Cemetery. Among the many noteworthy fighters he defeated had been Papke, Sullivan, Carpentier, Moreau, Harry Lewis, Frank Mantell, Leo Houck, Cyclone Johnny Thompson, and Jack Dillon. A sturdy, no-frills, rough-edged battler, Frank Klaus was the blueprint for the working-class ethic that outlined the best for Pittsburgh’s sports activities champions for many years to come back. He was inducted into the Worldwide Boxing Corridor of Fame in 2008. — Kenneth Bridgham